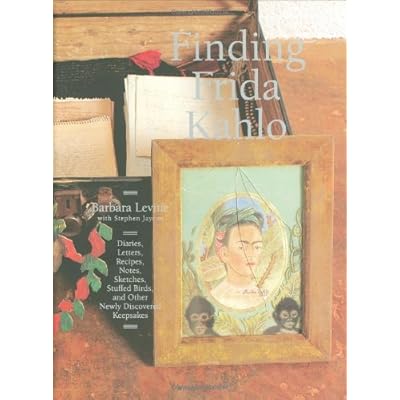

Finding Frida Kahlo/ Encontrando a Frida Kahlo (English and Spanish Edition)

Category: Books,Arts & Photography,History & Criticism

Finding Frida Kahlo/ Encontrando a Frida Kahlo (English and Spanish Edition) Details

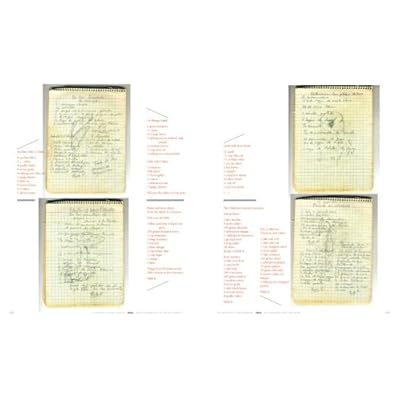

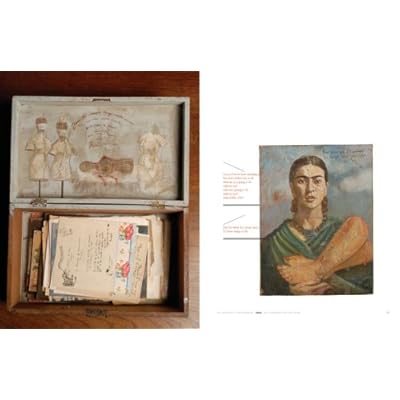

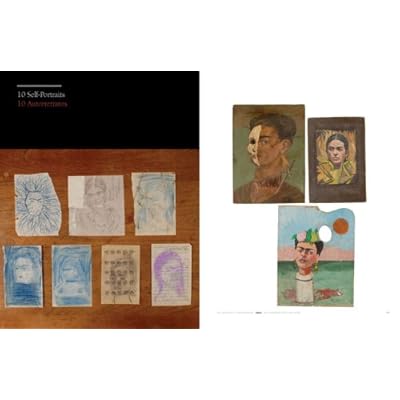

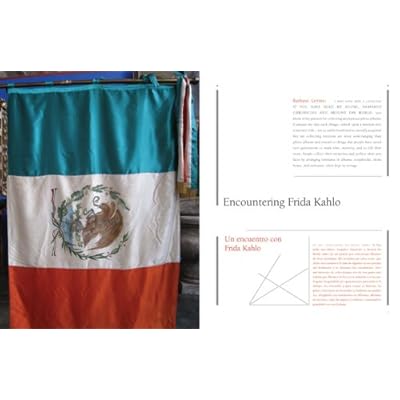

From Publishers Weekly Starred Review. Independent curator Levine (Around the World) encountered a mysterious, important and long-hidden collection of more than 1,200 of what are reputed to be Frida Kahlo's personal items in the back room of an antiques store in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. (The Associated Press has reported that the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Trust has charged that the materials in this book are forged. Mexican prosecutors are investigating.) Levine and Jaycox meticulously document the unpacking of the archive from five trunks, suitcases and boxes, and guide readers through the contents with reproductions of letters and diaries, and photos of Kahlo's drawings and personal effects. Levine finds it all illuminating, not only regarding Kahlo but also the universally human tendencies that the archive represents. Levine's interview with the antiques-store owners recounts their fascinating acquisition of the pieces while the visual exploration focuses on Kahlo's impassioned love and hatred for her husband, Diego Rivera, whom she calls an evil fat toad, and her anxiety over her amputated leg, which manifests itself in her obsession with flight (What do I want feet for/ If I have wings to fly). This beautiful book poetically offers a fresh look at one of art's iconic women, and though Kahlo is the protagonist of the project, Levine's journey includes us all. (Nov.) Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Read more Review "As a collector and archivist, Levine (former director of exhibitions, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) is particularly sensitive to the fragments of life one accumulates and how they can be interpreted by others. While sorting out her own life, she happened upon Frida Kahlo's personal archive, a treasure trove that had been lost for decades. This bilingual (English/Spanish) book is a record of her discovery, detailing both the objects themselves and the intimate relationships they evoked in viewers. Each object was photographed as it was unpacked and then returned to its original housing. In a very personal essay, the author charts revelations about this enigmatic artist yielded by the diary entries, recipes, sketches, and letters and a starkly annotated series of images of the techniques used for the amputation of her leg. VERDICT An illuminating find or an odd bit of miscellanea, depending upon the reader's interest in this artist's life, this book unravels for both author and reader the unique experience of a very human activity: storing away the little things by which we identify ourselves." -- Paula Frosch, Metropolitan Museum of Art,(August 19, 2009) --Library Journal - Paula Frosch, Metropolitan Museum of Art"The Noyolas have collaborated with Barbara Levine, a photography curator in San Miguel de Allende, on a book about the collection of more than 1,200 items, "Finding Frida Khalo: Diaries, Letters, Recipes, Notes, Sketches, Stuffed Birds, and Other Newly Discovered Keepsakes" (written with Stephen Jaycox and due this fal from Princeton Architectural Press). It shows the clutter that the Noyolas acquired, although the couple now keep the artifacts in neat vitrines and binders in their store, La Buhardilla (the Attic)." -- Eve M. Kahn,(June 26, 2009) --The New York Times"Beautifully documented, Finding Frida Kahlo includes lavish double-page spreads with detailed, translated captions that, for most of us, will be the closest we can get to the material. Despite a scrawled note on a used greeting card - ''I am nothing more than a passing bird. Everything is temporary; nothing lasts'' - Kahlo is destined to be remembered." -- Frances Atkinson,(August 14, 2009) --The Age Magazine (Australia)"The recent discovery in a Mexican factory of two trunks full of Frida Kahlo's personal artifacts -- carefully curated by Barbara Levine in Finding Frida Khalo -- opens up new perspectives on this endlessly fascinating cultural icon." (July 7th, 2009) --Best Hidden Gems Of The Year..., AmazonPolicing the legacy of artists can be a tough business. Nowhere is it tougher than in Mexico, where the magnetic, self-mythologizing painter Frida Kahlo (1907-54) shot from relative obscurity to iconic status only in the last quarter-century. Now, a festering dispute over a little-known archive of ephemera attributed to Kahlo has erupted into open warfare. Despite the tantalizing possibility that some or maybe even all the material is authentic, a sharp line has been drawn in the art historical sand. The story is marked by startling intimidation tactics that seem more a part of Tony Soprano's world than the genteel environs of scholarly argument. Aggressive bullying by Kahlo-establishment figures is so strange that it suggests something bigger: A fading ancient regime in Mexico might be coming to an end. Consider these four episodes: * Ruth Alvarado Rivera, now-deceased granddaughter of the great muralist Diego Rivera, Kahlo's husband, gave a 2005 interview to Mexico City's Reforma newspaper, illustrated with photographs of several small paintings never published before. One showed a slightly damaged little canvas in which Kahlo's head was affixed to the body of a slain deer. Retribution was swift and fierce. Reforma ran a story the next day denouncing as outrageous fakes the Kahlo works it published just 24 hours before. The assault was led by respected critic Raquel Tibol, an elder statesman of 19th and 20th century Mexican art history, whose books include a 1983 Kahlo survey. * A recent New York Times "Antiques" column published a freelancer's short item about a forthcoming book -- "Finding Frida Kahlo" by Barbara Levine, former exhibitions director at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and coming Nov. 1 from Princeton Architectural Press -- that includes the little Frida-deer painting, together with a previously unpublished archive of about 1,200 items (notebook pages, letters, diary entries, recipes, clothing, etc.). Within hours, a condemnatory letter was fired off to the newspaper from Carlos Phillips Olmedo, head of the executive committee of the Diego Rivera-Frida Kahlo Trust at the Central Bank of Mexico, guardian of the artists' copyrights. The letter, which the newspaper did not publish, protested "in no way do we recognize [the archive] as originals of Frida Kahlo." * A few weeks later in Mexico City, 11 prominent museum officials, gallery owners, art historians and artists signed an open letter decrying the imminent publication of these Kahlo "fakes." Citing no evidence for their explosive charge, the letter insisted that "the authorities and cultural institutions responsible for Mexico's artistic patrimony intervene immediately." * London's Art Newspaper wrote a story about the letter on Aug. 20, with the headline "Art Historians Assert That 'Lost Archive' of Paintings, Drawings and Diaries Are Forged." Mary-Anne Martin, longtime New York dealer in Latin American art, was quoted at length about the book. "In my view the publishers have been the victims of a gigantic hoax," said Martin, who also signed the letter. "I am astounded it has gone as far as it has." I'm astounded too -- but for different reasons. For one thing, Tibol, Phillips Olmedo and Martin have never laid eyes on the material they nonetheless insist is a blatant forgery. They've not seen the little painting of a deer, nor indeed any of the archive's 1,200 artifacts. For another, they and all the signatories to the open letter are cogs in the machinery of what could be called the Frida Kahlo Industry. That emergent enterprise took off a generation ago with the 1983 publication of the landmark "Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo" by Hayden Herrera, who also signed the joint letter. Her book performed an extraordinary feat -- a major scholarly work that also became a popular bestseller. Kahlo rightly metamorphosed from an artistic also-ran into an icon. The doubters might not have seen the purported archive, housed in a secure back room of a gallery in the central Mexican colonial town of San Miguel de Allende. But they do share a vested interest in Kahlo's robust market and the publishing business around it. A dealer specializing in Latin American art had better not cross a trust as powerful as the one devoted to Rivera and Kahlo, the two biggest names in Mexico's Modern art history. A historian wishing access to Kahlo material, including reproduction rights for books, is ill-advised to stray too far outside the officially approved field. An artist critically supported by that establishment needs to be careful in speaking out. Much is at stake, socially and financially. In Mexico, Kahlo is officially ranked an artist of the national patrimony, a formal endorsement foreign to American culture. Without official backing, an archive of previously unknown material faces high hurdles for acceptance. A preemptive, blindly made fraud claim is a political strategy, more authoritarian than authoritative. It recalls physician and former U.S. Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist asserting that Terri Schiavo, a comatose Florida woman, was not in a persistent vegetative state, based on his review of a videotape rather than the actual patient. Of course, three months later an autopsy confirmed that Schiavo had suffered severe, irreversible brain damage. Actual study of the Kahlo archive might prove similarly redemptive. A firsthand look As it happens, I have seen the disputed archive at the gallery -- not once, but three times in the last 18 months. Carlos Noyola and his wife, Leticia Fernández, art and antiquarian dealers in Monterrey, Mexico, for nearly four decades before moving to San Miguel a few years ago, acquired it in 2004, after a friend asked them to look at the battered little deer painting. It wasn't the only object attributed to Kahlo they were given to examine. There was also a traditional Michoacán-style floral batea -- a painted wooden tray -- decorated with a hot-pink flower bearing Frida's eyes and initials, a pure white flower bearing those of her notoriously philandering husband and a bright yellow flower hovering above Diego, anonymously and suggestively, like a woman's flouncing skirt. There was more. In fact, when all was said and done, the trove included 16 small oil paintings, 23 watercolors and pastels, 59 notebook pages (diary entries, recipes, etc.), 73 anatomical studies (some dated prior to Kahlo's disfiguring 1925 trolley accident), 128 pencil and crayon drawings, 129 illustrated prose-poems, and 230 letters to Carlos Pellicer, the Modernist poet and Frida's close confidant, many adorned with sketches -- skulls, insects, lizards, birds. Mostly it's ephemera, like a small box holding 11 taxidermy hummingbirds. There are pistols, such as an ornate 1870 Remington; a tricolor Mexican flag, its central white panel altered to celebrate Leon Trotsky ("Troski") and the Communist Party, to which Kahlo and Rivera belonged; hotel bills; photographs; receipts for sales of Rivera paintings; an embroidered huipil, a traditional Mayan blouse; an intimate diary, with one entry expressing Frida's intense (and unrequited) erotic attraction to lesbian ranchera singer Chavela Vargas; a French medical text on amputation, painted over with blood-red pigments; and more. The Kahlo cache is said to have been stored for 50 years in two wooden chests, a metal trunk, a wooden box and a battered suitcase. The forthcoming book, honest in its uncertainty about authenticity, tells a spare but reasonable history of ownership -- first given by the dying artist to sculptor Abraham Jimenez Lopez, a friend of Kahlo and Rivera's, in 1954, and then sold by him to attorney Manuel Marcue in 1979 -- as well as the Noyolas' initial efforts at verification. Is the archive genuine? I do not know. I've seen a majority of Kahlo's approved paintings, but I'm not an authority. It's certainly an odd assortment for a forger to bother with. The archive's drawings and paintings, all modest, cut a wide stylistic swath. Unlike Rivera, a virtuoso draftsman, the largely self-taught Kahlo had little innate facility. Her drawings are often notational, her paintings intentionally folkloric, sometimes even crude. Some archive works verge on academic, the last way one thinks of Kahlo. Various curios might be by other hands, memorabilia she saved. The most compelling painting shows an amputated leg wrapped in thorns or barbed wire and planted upside-down in a darkening Surrealist landscape. Sporting a winged foot and surrounded by a saw, ax, swallow and airplane, it's a secular ex-voto, traditional Mexican offering to a saint. Nothing is truly major, ranking with the great self-portraits. As a whole, though, the artist's obsessive self-regard rings true. Critic Ben Davis has noted that feminist Surrealism is only part of Kahlo's artistic story, one that helped catapult Herrera's marvelous biography because it corresponded with societal interests after the 1970s. Yet Kahlo's conscious "reiteration of the self, transformed into myth" is also a primary trait of Social Realist art in the 1920s and after -- the aesthetic language that created cults around Lenin, Stalin and Mao. This aspect of Kahlo's work shows her determined political sympathies for post-revolutionary Mexico, as well as for crafting her own reverential following. What comes next Nobody was more resistant to Frida's worshipful veneration than Dolores Olmedo Patiño, the rich and powerful collector to whom Rivera, reputed to have been her youthful lover, gave posthumous control of his and Kahlo's estates. The Rivera-Kahlo Trust's Carlos Phillips Olmedo is her son. I made the first of several visits to Olmedo's 16th century hacienda in Xochimilco in 1984, as she was planning to turn the estate into a museum. (The Museo Dolores Olmedo opened 10 years later.) Conceived as a Rivera shrine, it features 145 of the painter's works; 900 pre-Columbian sculptures plus folk crafts, which he championed for their indigenous character; and engravings by Angelina Beloff, his conventionally talented first wife. Each time I would ask to see Olmedo's 25 Kahlo paintings -- the largest collection anywhere, about one-eighth of Kahlo's output. She would frown, dismiss them as minor and finally relent. Usually the paintings were kept in an out-of-the-way room, lined up on the floor facing the wall. "In the future, Kahlo will fade away," Olmedo once told The Times. Just before his 1957 death, Rivera instructed Olmedo not to unseal, for a period of 15 years, the many rooms packed with Kahlo's belongings left behind at Casa Azul, the famous "blue house" in Coyoacan where the artist lived. In fact, Olmedo never unsealed them. Finally opened after her death in 2002, they yielded 28,000 new documents, 5,800 photos, 300 garments and many paintings and drawings. Kahlo was a pack rat. Perhaps their 2004 unveiling coaxed the Noyola's archive out of hiding. New information always comes to light. Ferocious yet cavalier denunciations don't discredit the uncertain archive, only the entrenched establishment that utters them. Generational change is wrenching -- a woolly mammoth bellows in a tar pit -- but the tumult shows that it's certainly underway. Brass-knuckles intimidation tactics are clear evidence for what should happen next. The archive, compelling enough for serious further study, needs sunshine -- difficult to find anywhere, but certainly unavailable in official Mexico. The Noyolas have done interesting, basic forensic research and have always been open to any scholar who would like to actually see the archive. They should move it to more neutral ground outside the country. Here's the irony: Had it been accepted as official national patrimony, the archive would not be allowed to leave Mexico. The nation's loss could be art's gain. --L.A. Times"I concur with Knight, only serious scholarship will tell the tale and I look forward to seeing how this one plays out..." -- Raul Gutierrez --Heading East"The book is wonderful. Reading the translated letters by Fridaher cursing Diego, longing for him reveals the kind of relationship the two artists had with each other. Her erotic drawings and others are packed with symbolism and cryptic hints at dual meanings allowing for much interpretation. The design of the book is beautiful, but how could it not be? It was designed by Martin Venezky and his Appetite Engineers design shop in San Francisco." -- John Foster --Accidental Mysteries"Finding Frida Kahlo by Barbara Levine and Stephen Jaycox is not necessarily what one might expect. Neither a biography nor document about Kahlo's work, this book is an itemized account of the contents of Kahlo's alleged personal archives, found in an antiques store in Mexico's San Miguel de Allende. Inside an old suitcase, two wooden chests and a box, and a metal trunk are letters, diary pages, stuffed hummingbirds, small pieces of artwork, and a variety of other ephemeral fragments of Frida Kahlo's life. Translations of the notes serve as annotations to the photographs of the contents, whose authenticity is still in dispute. But in some ways this book is more about the very notion of personal archives and collections than the famous Mexican artist. How are we reflected in what we leave behind?" --Mocoloco"Independent curator Levine (Around the World) encountered a mysterious, important and long-hidden collection of more than 1,200 of what are reputed to be Frida Kahlos personal items in the back room of an antiques store in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. (The Associated Press has reported that the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Trust has charged that the materials in this book are forged. Mexican prosecutors are investigating.) Levine and Jaycox meticulously document the unpacking of the archive from five trunks, suitcases and boxes, and guide readers through the contents with reproductions of letters and diaries, and photos of Kahlos drawings and personal effects. Levine finds it all illuminating, not only regarding Kahlo but also the universally human tendencies that the archive represents. Levines interview with the antiques-store owners recounts their fascinating acquisition of the pieces while the visual exploration focuses on Kahlos impassioned love and hatred for her husband, Diego Rivera, whom she calls an evil fat toad, and her anxiety over her amputated leg, which manifests itself in her obsession with flight (What do I want feet for/ If I have wings to fly). This beautiful book poetically offers a fresh look at one of arts iconic women, and though Kahlo is the protagonist of the project, Levines journey includes us all. (Nov.)" --Publishers Weekly"A verbal civil war continues to rage in the Mexican art world as Kahlo experts argue over the authenticity of a once obscure Kahlo archive that will be featured in Finding Frida Kahlo, a book by Barbara Levine due out from Princeton Architectural Press in November." --Artinfo Read more About the Author Barbara Levine runs project b, a curatorial services company specializing in archives, collections, vernacular photography, and artist projects. She was formerly director of exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Read more

Reviews

REVIEW OF FINDING FRIDA KAHLOBy Gloria F. OrensteinProfessor of Comparative Literature and Gender StudiesUniv. of Southern CaliforniaLos Angeles, CA. When I was in Mexico City doing research for my article: "Frida Kahlo: Painting For Miracles" which was published in the Fall 1973 issue of THE FEMINIST ART JOURNAL, I could only obtain very limited information on Frida Kahlo's work. What I did see was on display at La Casa Azul in Coyoacan. That was all I was able to see at the time. The diary was on display, and house was completely furnished. However, at that time I was told that there were many things that could not be shown to the public until fifty years after Diego Rivera had died, and that many of them contained expressions of anger which should be kept from the public until that half century had passed. I was told this by curators of museums and galleries in Mexico City. Over the years I have been following the exhibitions and criticism on Frida Kahlo, and naturally this cache of materials that has been revealed in Barbara Levine's exquisite publication, FINDING FRIDA KAHLO, is of extreme interest to me. Obviously, I am in no position to speak to the authenticity of the various items in this treasure trove, but I did find it important to learn that those who denied their authenticity have not actually seen the materials, and that those who authenticated some of them have, in fact, subjected them to the tests required to make pronouncements regarding their authenticity. I have been showing the book to my students, hoping to expose them to the complexity of issues surrounding these decisions. To me, this cache is much like a letter in a bottle put out to sea in the hopes that it will reach the right person on a distant shore at precisely the right moment. Clearly Barbara Levine, by the lucidity with which she has elaborated on the process of transmission that brought these materials into her possession, and by the clarity with which she has presented the peregrinations of the ongoing inquiries into the history of their ownership, is precisely the right person to have received the message contained in the metaphorical bottle. Only time will tell whether the complete contents of this collection will be authenticated, but for the moment, it is a fascinating conundrum, which will puzzle many art history sleuths who will apply their cutting edge techniques, theories, and disputes to its resolution for a long time to comeBecause of what was told to me in the early seventies, I am not surprised that these materials (and those in another collection that I have also seen in San Miguel de Allende) have turned up just as the fifty years since Diego Rivera's death have passed, so that (whether they turn out to be authentic or not) they might be revealed to the public at precisely this time. When I think back to 1973, I recall a moment in which Art Historians and Surrealist Scholars in the states had barely any knowledge of Frida Kahlo (myself included....I am a feminist scholar of Surrealism (from Comparative Literature), but not an Art Historian), and I simply marvel at the way Frida Kahlo's work has attained world acclaim in just a few decades, and has finally been included in the history of western art. This is due in large part to the dedicated work of many feminist Art Historians as well as to that of all the others specialists who have been involved in these often extremely subtle, complex, and delicate matters.